The Great Starvation

The Great Starvation or the Great Hunger refers to the period of mass suffering, starvation and death in Ireland between 1845 and 1852. This exhibition tells the story of what happened and why.

After centuries of British colonial rule, most of the native rural catholic Irish had been dispossessed of their ancestral land. Many lived in extreme poverty and depended on the potato as their main (and often their only) food source for survival. The threat of starvation was never far away.

Centuries of British invasions, land confiscations and anti-catholic laws had reduced the country and it's people to levels of poverty not seen in other parts of Europe.

At the same time, Britain was booming and in the throes of the industrial revolution. Ireland (forcibly) was part of the United Kingdom at this time and might have expected to benefit accordingly. But this was not to be.

Britain had always treated Ireland harshly. This time would be no different.

Massive humanitarian aid was required, and quickly. Instead the British Government chose piecemeal and slowly. Their overriding concern was not to disrupt market forces, and food continued to be exported to Britain as the Irish starved. They raised taxes and washed their hands of the crisis when it was still only half way through.

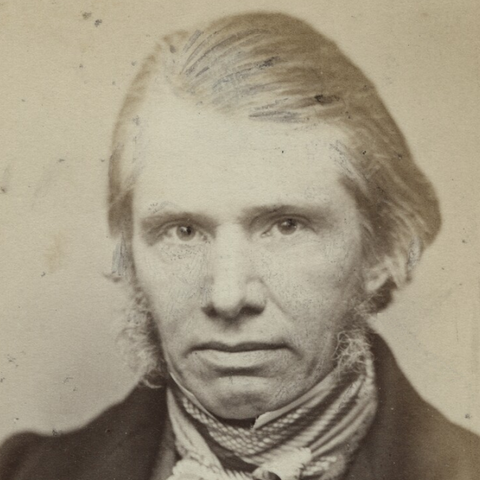

Daniel O'Connell (only known photo 1844)

At the start of the potato crops multiple seasons of failures, Daniel O’Connell warned the British government that unless they intervened quickly to provide relief, there would be a ‘death-dealing famine’ in the country. His prediction proved correct. The Government was massively informed by witnesses on the ground. Clergy, Relief Administrators, Notable Citizens, Newspaper men etc.

The Great Starvation / Great Hunger in Ireland caused great devastation. At least a million died, perhaps even 1.5 million...we will never know the true figure. Millions more were forced to feel the country. The population of the island has never recovered. From a population of between 8 and 9 million in 1845, a steady decline ensued for the next century and a half as other European populations grew.

Mote Park County Roscommon, the seat of the Crofton Family from the 16th century

Whether resident or absentee, many landlords administered their estates in an extremely short-sighted fashion. Their priority was to extort the highest possible rents, and only a minority were ‘improving’ landlords who re-invested in their estates. Some landlords preferred to rent their estate to “middlemen” and so avoid having to deal with a multitude of tenants. In order to maximise his return, the middleman in turn would divide the land up into many small pieces of ground, usually no more than an acre, and let them annually to peasant farmers for a high rent.

Irish Famine Museum / Ireland's Great Hunger Exhibition and Film, 2nd Floor, Stephens Green Shopping Centre, Dublin.

Additional Reading as Follows:

The Great Hunger in Ireland: A Tragic Saga of Suffering, Resilience, and Legacy

Introduction:

The Great Starvation or Ireland's Great Hunger, also known as the Irish Potato Famine, is a harrowing chapter in Irish history that left an indelible mark on the nation and its people. Lasting from 1845 to 1852, this catastrophic event resulted in the deaths of approximately one million Irish men, women, and children, while prompting the emigration of another million. In this article, we delve into the story of the Great Hunger in Ireland, exploring its causes, consequences, and enduring legacy.

The Potato Blight and the Famine's Origins:

The immediate cause of the Great Starvation was the devastating potato blight that swept across Ireland in the mid-19th century. Phytophthora infestans, a fungal pathogen, ravaged potato crops, which served as the primary staple food for a significant portion of the Irish population, particularly the rural poor.

The Irish peasantry, comprised largely of tenant farmers, depended heavily on potatoes for sustenance. The crop's high yield and nutritional value made it an essential component of the Irish diet, especially in regions where land was scarce and agricultural practices were rudimentary.

However, the overreliance on potatoes made Ireland susceptible to catastrophe when the blight struck. Beginning in 1845, successive potato harvests failed, plunging the country into a state of agricultural crisis. The blight persisted for several years, leading to widespread famine and devastation.

Socio-Economic Factors:

While the potato blight served as the immediate trigger for the famine, its underlying causes were rooted in Ireland's socio-economic and political landscape. Centuries of colonialism, land inequality, and economic exploitation had left the Irish population vulnerable and impoverished.

The system of landlordism, which prevailed throughout much of Ireland, exacerbated the plight of the rural poor. Many tenant farmers lived on small plots of land, subject to exorbitant rents and arbitrary evictions by absentee landlords. The consolidation of land into large estates further marginalized tenant farmers, leaving them with little recourse when crops failed.

Moreover, British colonial policies had long favored the interests of landowners and absentee landlords over those of the Irish peasantry. The imposition of high rents, the exportation of foodstuffs, and the lack of investment in infrastructure and relief efforts all contributed to the severity of the famine.

Charles Trevelyan, British civil servant in charge of Relief policy

British Response and Relief Efforts:

The response of the British government to Ireland's Great Starvation has been the subject of much criticism and debate. Despite being the ruling authority in Ireland at the time, the British government's policies exacerbated the crisis and compounded the suffering of the Irish population.

Initially, the British government adopted a laissez-faire approach, believing that market forces would mitigate the effects of the famine. However, this hands-off approach proved disastrous, as relief efforts were woefully inadequate to address the scale of the crisis.

The introduction of relief measures, such as soup kitchens and public works projects, provided some temporary relief to those affected by the famine. However, these efforts were insufficient to prevent widespread suffering and loss of life. Moreover, bureaucratic inefficiencies, corruption, and logistical challenges hindered the effective distribution of aid.

Emigration and the Diaspora:

As Ireland's Great Hunger worsened and conditions in Ireland became increasingly dire, millions of Irish men, women, and children chose to emigrate in search of a better life abroad. Emigration became a mass exodus, with ships packed full of desperate individuals leaving Irish shores for distant lands.

The United States and Canada emerged as primary destinations for Irish emigrants, offering the promise of opportunity and a fresh start. However, the journey was perilous, and many emigrants perished en route due to disease, malnutrition, and overcrowding.

The Irish diaspora that emerged in the wake of the famine has had a profound impact on global history and culture. Irish immigrants brought with them their traditions, language, and resilience, leaving an indelible mark on the countries they settled in. Today, the Irish diaspora spans the globe, with millions of individuals tracing their ancestry back to those who fled the famine-stricken shores of Ireland.

Social and Cultural Impact:

The Great Hunger in Ireland had profound social and cultural implications for Ireland, shaping the nation's identity and collective memory. The trauma of the famine left deep scars on the Irish psyche, influencing attitudes towards authority, resilience, and community solidarity.

The memory of the famine became a central motif in Irish literature, music, and art, serving as a potent symbol of suffering and endurance. Writers such as William Carleton, Samuel Ferguson, and William Butler Yeats captured the anguish of the famine and its aftermath in their works, ensuring that the tragedy would not be forgotten.

Moreover, the famine deepened divisions within Irish society, exacerbating tensions between landlords and tenants, Catholics and Protestants, and rural and urban populations. The legacy of resentment towards British rule and perceived neglect persists to this day, fueling nationalist sentiment and political movements seeking Irish independence.

Legacy and Remembrance:

Despite the passage of time, the legacy of the Ireland's Great Hunger endures, serving as a solemn reminder of the fragility of human existence and the importance of solidarity in times of crisis. Efforts to commemorate the victims of the famine have gained momentum in recent years, with initiatives such as the National Famine Commemoration and the development of famine memorials and museums.

These efforts seek to ensure that the memory of the famine remains alive in the national consciousness, honoring the lives lost and the resilience of those who survived. By remembering the Great Hunger, we reaffirm our commitment to building a more just and compassionate world, where hunger and injustice are eradicated, and the dignity of every human being is upheld.

Conclusion:

Ireland's Great Hunger stands as a tragic chapter in Irish history, marked by profound loss, suffering, and resilience. As we reflect on the story of the famine, let us honor the memory of those who perished by working towards a future where hunger and inequality are eradicated, and the lessons of the past are not forgotten. In remembering the Great Hunger in Ireland, we affirm our shared humanity and our responsibility to create a world where all people can thrive.